| |

| This article is part of the series on the military of the Byzantine Empire, 330–1453 AD | |

| Structural history | |

|---|---|

| Byzantine army (Generals): East Roman army, Middle Byzantine army (themes •tagmata • Hetaireia), Komnenian Byzantine army(pronoia), Palaiologan Byzantine army (allagia) •Varangian Guard | |

| Byzantine navy (Admirals):Greek fire • Dromon | |

| Campaign history | |

| Lists of wars and revolts and civil wars | |

| Strategy and tactics | |

| Tactics • Siege warfare • Military manuals •Fortifications (Walls of Constantinople) | |

The East Roman army refers to the army of the Eastern section of the Roman Empire, from the empire's definitive split in 395 AD to the army's reorganization by themesafter the permanent loss of Syria, Palestine and Egypt to the Arabs in the 7th century (during the Byzantine-Arab Wars). The East Roman army is thus the intermediate phase between the Late Roman army of the 4th century and the Byzantine army of the 7th century onwards.

The Roman Army of the 4th century, both Eastern and Western, is described in detail in the article Late Roman army. In its essential features, the East Roman army's organisation remained similar to the 4th century configuration. This article focuses on changes to that configuration during the 5th and 6th centuries.

The bulk of the evidence for the East Roman army is from the period of emperor Justinian I (reigned 527-65), who undertook a major programme to reconquer the lost territories of the fallen Western Roman Empire, which had collapsed in 476AD and been replaced by barbarian successor kingdoms. Justinian succeeded in recapturing Italy, Africa and southern Spain. These wars, and the career of Justinian's generalissimo, Belisarius, are described in detail by the 6th century historian Procopius.Much of our evidence for the East Roman army's deployments at the end of the 4th century is contained in a single document, the Notitia Dignitatum, compiled c395-420, a manual of all late Roman public offices, military and civil. The main deficiency with the Notitia is that it lacks any personnel figures so as to render estimates of army size impossible. However, the Notitia remains the central source on the late Army's structure due to the dearth of other evidence.

The third major source for the East Roman army are the legal codes published in the East Roman empire in the 5th and 6th centuries: the Theodosian code (438) and the Corpus Iuris Civilis (528-39). These compilations of Roman laws dating from the 4th century contain numerous imperial decrees relating to all aspects of the regulation and administration of the late army.

Background

In 395, the death of the last sole Roman emperor, Theodosius I (r. 379-95), led to the final split of the empire into two political entities, the West (Occidentale) and the East (Orientale). The system of dual emperors (called Augusti after the founder of the empire, Augustus) had been instituted a century earlier by the great reforming emperor Diocletian (r.284-305). But it had never been envisaged as a political separation, purely as an administrative and military convenience. Decrees issued by either emperor were valid in both halves and the successor of each Augustus required the recognition of the other. The empire was reunited in single hands twice: under Constantine I (r. 312-37) and Theodosius himself.

But the division into two sections recognized a growing cultural divergence. The common language of the East had always been Greek, while the West was Latin-speaking. This was not per se a significant division, as the empire had long been a fusion of Greek and Roman cultures (classical civilisation) and the Roman ruling class was entirely bilingual. But the rise of Christianity strained that unity, as the cult was always much more widespread in the East than in the West, which was still largely pagan in 395. Constantine's massive reconstruction of the city of Byzantium intoConstantinople, a second capital to rival Rome, led to the establishment of a separate eastern court and bureaucracy.

Finally, the political split became complete with the collapse of the Western empire in the early 5th century and its replacement by a number of barbarian Germanic kingdoms. The Western army was dissolved and was incorporated into the barbaric kingdoms. The Eastern empire and army, on the other hand, continued intact until the Arab invasions in the 7th century. These deprived the East Roman empire of its dominions in the Middle East and North Africa, especially Egypt.

The Army of Theodosius I (395)

Numbers

The size of the Eastern army in 395 is controversial because the size of individual regiments is not known with any certainty. Plausible estimates of the size of the whole 4th century army (excluding fleets) range from c400,000[1] to c600,000.[2] This would place the Eastern army in the rough range 200,000 to 300,000, since the army of each division of the empire was roughly equal.[3]

The higher end of the range is provided by the late 6th century military historian Agathias, who gives a global total of 645,000 effectives for the army "in the old days", presumed to mean when the empire was united.[4] This figure probably includes fleets, giving a total of c600,000 for the army alone. Agathias is supported by A.H.M. Jones' Later Roman Empire (1964), which contains the fundamental study of the late Roman army. Jones calculated a similar total of 600,000 (exc. fleets) by applying his own estimates of unit strength to the units listed in the Notitia Dignitatum.[2] Following Jones, Treadgold suggests 300,000 for the East in 395.[5]

But there are strong reasons to view 200,000 as more likely:

- Jones' assumptions about unit strengths, based on papyri evidence from Egypt, are probably too high. A rigorous reassessment of the evidence by R. Duncan-Jones concluded that Jones had overestimated unit sizes by 2-5 times.[6]

- The evidence is that regiments were typically one-third understrength in the 4th century.[7] Thus Agathias' 600,000 on paper (if it is based on official figures at all) may in reality have translated into only 400,000 actual troops on the ground.

- Agathias gives a figure of 150,000 for the army in his own time (late 6th c.) which is more likely to be accurate than his figures for the 4th century. If Agathias' 4th c. and 6th c. figures are taken together, they would imply that Justinian's empire was defended by only half the troops that supposedly defended the earlier empire, despite having to cover even more territory (the reconquered provinces of Italy, Africa and S. Spain), which seems inherently unlikely.

The discrepancy in army size estimates is mainly due to uncertainty about the size of limitaneiregiments, as can be seen by the wide range of estimates in the table below. Jones suggests limitaneiregiments had a similar size to Principate auxilia regiments, averaging 500 men each.[8] More recent work, which includes new archaeological evidence, tends to the view that units were much smaller, perhaps averaging 250.[6][9]

There is less dispute about comitatus regiments, because of more evidence. Treadgold estimates the 5 comitatus armies of the East as containing c20,000 men each, for a total of c100,000, which constitutes either one-third or one-half of the total army.[5]

About one third of the army units in the Notitia are cavalry, but cavalry numbers were less than that proportion of the total because cavalry unit sizes were smaller.[10] The available evidence suggests that the proportion of cavalry was about one-fifth of the total effectives: in 478, a comitatus of 38,000 men contained 8,000 cavalry (21%).[11]

Command structure

The later 4th century army contained three types of army group: (1) Imperial escort armies (comitatus praesentales). These were ordinarily based near Constantinople, but often accompanied the emperors on campaign. (2) Regional armies (comitatus). These were based in strategic regions, on or near the frontiers. (3) Border armies (exercitus limitanei). These were based on the frontiers themselves.

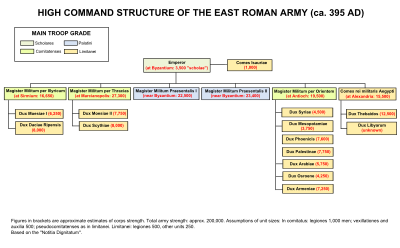

The command structure of the Eastern army, as recorded in the Notitia Dignitatum, is represented diagramatically in the organisation chart (above).

By the end of the 4th century, there were 2 comitatus praesentales in the East. They wintered near Constantinople at Nicaea and Nicomedia. Each was commanded by a magister militum ("master of soldiers", the highest military rank) Each magister was assisted by a deputy called a vicarius.[12]

There were 3 major regional comitatus, also with apparently settled winter bases: Oriens (based atAntioch), Thraciae (Marcianopolis), Illyricum (Sirmium) plus two smaller forces in Aegyptus (Alexandria) and Isauria. The large comitatus were commanded by magistri, the smaller ones bycomites. All five reported direct to the eastern Augustus. This structure remained essentially intact until the 6th century.[12]

Regiments

Regiments were classified according to whether they were attached to the comitatus armies (comitatenses) or border forces (limitanei). Of the comitatenses regiments, about half were palatini(literally: "of the palace"), an elite grade.

The strength of army regiments is very uncertain and may have varied over the 5th/6th centuries. Size may also have varied depending on the grade of the regiment. The table below gives some recent estimates of unit strength, by unit type and grade:

| Cavalry unit type | Comitatenses (inc. palatini) | Limitanei | XXXXX | Infantry unit type | Comitatenses (inc. palatini) | Limitanei |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | 120-500 | Auxilia | 800-1,200 or 400-600 | 400-600 | ||

| Cuneus | 200-300 | Cohors | 160-500 | |||

| Equites | 80-300 | Legio | 800-1,200 | 500 | ||

| Schola | 500 | Milites | 200-300 | |||

| Vexillatio | 400-600 | Numerus | 200-300 |

The overall picture is that comitatenses units were either c1,000 or c500 strong. Limitanei units would appear to average about 250 effectives. But much uncertainty remains, especially regarding the size of limitanei regiments, as can be seen by the wide ranges of the size estimates.

Scholae

The Scholae Palatinae were elite cavalry regiments that acted as imperial escorts. At the end of the 4th c., there were 7scholae (3,500 men) in the East. They were outside the normal military chain of command as they did not belong to thecomitatus praesentales and reported to the magister officiorum, a civilian official.[14] However, this was probably only for administrative purposes: on campaign, the tribunes (regimental commanders) of the scholae probably reported direct to the emperor himself. 40 select troops from thescholae, called candidati from their white uniforms, acted as the emperor's personal bodyguards.[15]

Comitatenses

Comitatenses cavalry regiments were known as vexillationes, infantry regiments as either legiones or auxilia.[16] About half the regiments in the comitatus, both cavalry and infantry, were classified as palatini. They were concentrated in the comitatus praesentales (80% of regiments) and constituted a minority of the regional comitatus (14%).[17] The palatini were an elite group with higher status and probably pay.[18]

The majority of cavalry regiments in the comitatus were traditional melee formations (61%). These regiments were denoted scutarii, stablesiani or promoti, probably honorific titles rather than descriptions of function. 24% of regiments were light cavalry: equites Dalmatae, Mauri and sagittarii(mounted archers). 15% were heavily armoured shock charge cavalry: cataphracti and clibanarii[10]

Limitanei

In the limitanei, most types of regiment are present, including the old-style alae and cohortes of the Principate auxilia.

Recruitment

In 395, the army used Latin as its operating language. This continued to be the case into the late 6th century, despite the fact that Greek was the common language of the Eastern empire.[19] This was not simply due to tradition, but also to the fact that about half the Eastern army continued to be recruited in the Latin-speaking Danubian regions of the Eastern empire. An analysis of known origins ofcomitatenses in the period 350-476 shows that in the Eastern army, the Danubian regions provided 54% of the total sample, despite constituting just 2 of the 7 eastern dioceses (administrative divisions): Dacia and Thracia.[20] These regions continued to be the prime recruiting grounds for the East Roman army e.g. the emperor Justin I (r. 518-27), uncle of Justinian I, was a Latin-speaking peasant who never learnt to speak more than rudimentary Greek. The Romanized Thracian (Thraco-Roman) and Illyrian inhabitants of those regions, who came to be known as Vlachs by foreigners in theMiddle Ages, retained the Roman name (Romanians) and the Latin tongue.

Citations

- ^ Elton (1996) 120

- ^ a b Jones (1964) 683

- ^ Heather (2005) 247

- ^ Agathias History V.13.7-8; Jones (1964) 680

- ^ a b Treadgold (1995) 45

- ^ a b Duncan-Jones (1990) 105-17

- ^ Elton (1996)

- ^ Jones (1964) 681-2

- ^ Mattingley (2006) 239

- ^ a b Elton (1996) 106

- ^ Elton (1996) 105-6

- ^ a b Jones (1964) 609

- ^ Data from Duncan-Jones (1990) 105-17; Elton (1996) 89; Goldsworthy (2005) 206; Mattingly (2006) 239

- ^ Notitia Dignitatum Titles IX and XI

- ^ Jones (1964) 613

- ^ Elton (1996) 89

- ^ Notitia Dignitatum Orientalis Titles V - IX inc.

- ^ Elton (1996) 94

- ^ Maurice Strategikon

- ^ Elton (1996) 134

[edit]References

- Duncan-Jones, Richard (1990). Structure and Scale in the Roman Economy.

- Duncan-Jones, Richard (1994). Money and Government in the Roman Empire.

- Elton, Hugh (1996). Warfare in Roman Europe, AD 350-425. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815241-5.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2000). Roman Warfare.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2005). Complete Roman Army.

- Heather, Peter (2005). Fall of the Roman Empire.

- Isaac, B. (1992). Limits of Empire.

- Jones, A.H.M. (1964). Later Roman Empire.

- Luttwak, Edward (1976). Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire.

- Treadgold, Warren (1995). Byzantium and its Army (284-1081).

- Wacher, John (1988). The Roman World.